For a plant humans have grown and transported around the world for thousands of years—utilizing its precious seeds, flowers, resin, and fibers in myriad ways—we sure don’t know much about cannabis. Only recently have scientists begun to identify its chemical compounds and other properties with any degree of accuracy. Patients and doctors have designed their own ad hoc treatments, but serious clinical trials are few and far between, both in the U.S. and abroad.

As scientists and researchers begin to unravel the tangled and convoluted codes of cannabis genotypes, new light is shed on the most infamously hybridized plant on the planet. For farmers and breeders who want to settle scores, DNA-mapping projects will provide more clarity about what’s what in the cannasphere and who really developed some of the industry’s most prized strains.

For now, though, as you’re perusing the never-ending menu of flowers, oils, and edibles at the local cannabis shop, remember cannabis is still a genetic work in progress.

Constructing a weed galaxy

Mowgli Holmes has been working to map cannabis genotypes at his Portland, Oregon, company Phylos since 2014. As cannabis growers across the world send samples for testing, Phylos employs modern molecular genetics and computational biology to create a “galaxy” visually representing hundreds of cannabis cultivars and how they relate to each other. Think of it as a slowly unfolding map of the cannabis genome, in all its 3D glory.

“It’s interesting how diverse and interbred cannabis is, and its galaxy is this tangled hairball that shows intense hybridization,” said Holmes. “Everything has been crossed and crossed in this atypical breeding situation that is very unlike any other crop. So, we have this weird population that is diverse, but blended together in this complicated soup.”

He pointed out the landrace strains, the original, indigenous cultivars, essentially have been bred out of existence. As people spread cannabis seeds across the globe, strains from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East began sprouting in environments vastly different from their native soils. When growers began breeding cannabis strains together to maximize THC and other desirable attributes, some of their inherent traits were lost in the shuffle.

When a grower sends in a strain to be identified, Phylos puts it through a DNA sequencing process and then gives the genotype a location in the Phylos Galaxy, which is determined by how closely its DNA is related to other samples already plotted. The genotype report also is available and shows the closest genetic relatives, population profile, and other characteristics. Using the report as a baseline, growers can certify their sample and give customers more assurance they are getting the same medicine each time they buy a particular cut. However, even when plants are genetically identical, the growing environment impacts the appearance, smell, taste, and effects. So, the genotype has a range of possible traits, but other variables determine the results. DNA is a factor, but not the final word.

“The problem with this data [from the genetic analysis] is that there are so many varieties and such a tangle, there is no such thing as a strain or stable seed lines,” Holmes explained. “In normal agriculture we have genetically stable plants, but this isn’t the case with cannabis. Seeds are unique, and every plant is its own special snowflake with its own chemical diversity.”

One of the difficulties raised by all the unique, irregular seeds floating around is a considerable and coordinated effort is required to sort out the best phenotypes from the rest. Of course, some intrepid farmers look at the challenge and jump in head-first.

Breeding next-gen strains

As chief executive officer for Humboldt Seed Company, Nathaniel Pennington has a reputation to protect. Not only for his company, but also the NorCal region he represents. Since the 1960s or so, the Emerald Triangle arguably has been the most important place on the planet for cannabis breeding, strain development, and propagation. Indeed, many of the powerhouse strains that established Amsterdam as weed capital of the world were developed in the shadows of the Emerald Triangle. This massive, interconnected, and off-grid science experiment is still alive and well today.

In 2018, Humboldt Seed partnered with Oakland’s Dark Heart Nursery on a “mega pheno-hunt” designed to pick out the unicorns—the most vigorous, unique, and outstanding cannabis plants—from a collection of about 10,000individual plants (“phenos”) they’ve tracked over the past year. For Dark Heart, the hunt is an opportunity to identify new and promising strains and to develop a closer relationship with a top-notch genetics company. With the plants in full bloom, Humboldt Seed and Dark Heart, along with a cadre of plant science gurus from around the U.S., visited farms to get an up-close look at thousands of plants, searching for the best of the best.

Because cannabis has been under prohibition for so long, Pennington explained, there haven’t been organized, large-scale efforts to explore breeding and phenotype selection, using precise rating systems and tracking chemotype variations. Chemotype is the chemical composition, phenotype is the outward expression, and genotype is the genetic thumbprint. “And then when you have something wonderful, where all three of those come together, that’s a Dream-O-Type…that’s the unicorn,” Pennington said.

Pennington founded Humboldt Seed almost twenty years ago, teaming up with Benjamin Lind and Beau Quinter some years later. Walking around a farm with any of the three men can turn into a geeked-out genetics discussion at the drop of a nugg. Looking through a line of blooming bushes on the Humboldt Seed farm, Lind picked out some of his favorites—pointing out the bright-white pistils and deep green and purple hues on some plants and the tight internodal spacing and bud structures on others.

When growers use the same mothers and clones to propagate their crops year after year, the plants eventually lose some of their vigor and desirable traits. By contrast, Humboldt Seed creates new seeds, strains, and genetics by using pollination chambers where one male plant is surrounded by dozens of females that produce hundreds and thousands of new seeds, each with its own boundless potential.

One of Pennington’s favorite tools on the pheno hunt is Orange Photonics’ LightLab Analyzer, a portable testing kit that uses liquid chromatography with spectroscopy to separate and measure chemical compounds. The device reports data for six major cannabinoids and terpene intensity. Somewhat remarkably, the results are delivered in about ten to fifteen minutes.

“Using the LightLab and marker-assisted breeding, and the fact we can share things more openly, we’re about to hit lightspeed compared to how it’s been moving along in genetics advancements,” Pennington said. “It’s definitely an exciting time to be in the industry and on the creative end of cannabis development.”

In Humboldt Seed, Dark Heart sees a company with twenty years of experience in producing unique, stable genetics, and an ongoing opportunity to offer its customers sturdy -and exotic new strains. In Dark Heart, Humboldt Seed sees one of the most established and reputable clone producers in the state, which connects it more directly with home and commercial growers who provide feedback and de facto marketing for its new strains. Dark Heart also keeps clones of its Humboldt Seed strains in its tissue culture lab, preserving the unique genetics indefinitely.

“Humboldt Seed has identified some really interesting, unique terpene profiles that create a distinguished product at retail,” said Dark Heart founder and CEO Dan Grace.

Commercial agriculture, biotech, and other established scientific communities and industries are beginning to take breeding and production processes in new directions, based on time-tested techniques that areused for other crops. Holmes believes the current cannabis flower market is driven by novelties and new flavors—like Humboldt Seed’s “Blueberry Muffin” strain—that vary by region and state. Eventually, Holmes predicted, these “hype” strains will take a back seat to ones more practical for commercial farm operations to grow on a consistent, reliable basis.

Indeed, once modern commercial breeding tools are brought to bear on cannabis, breeders won’t focus so much on plants with loud noses and couch-lock qualities but instead will seek out high-yield cultivars that are pest-and mold-resistant, less water-intensive, and optimized for specific growing conditions.

“But that stuff hasn’t come to market yet,” said Holmes. “As they do, those strains will dominate.”

A genetic archive of cannabis strains

Now and again, stories surface about growers who submit a flower sample with unique, valuable attributes—a high percentage of a cannabinoid like THCv or CBN, for instance—to a lab, which reports the exciting results back to the grower a few days (or weeks) later. Sadly, the grower never took a clone from that specific phenotype, so its distinctive genetic attributes are preserved only in a lowly lab report.

To prevent the scenario, some farmers are beginning to hedge their genetic bets by using tissue culture to preserve phenotypes deemed unique and valuable. Founded in 2007, Dark Heart is one of the oldest cannabis nurseries in the U.S., and over the years Grace has had to revise and update his business model to meet the needs of indoor, outdoor, and greenhouse growers.

“The hard thing with the industry this year is the ways people are cultivating have changed a lot. We’re seeing more scale, different cultivating regions, and different types of systems: field cultivation, mechanized cultivation, and traditional craft cultivation,” he said. “So, we need to figure out what cultivation is going to look like and what varietals are going to be good for different systems and regions.”

Beyond offering farmers a rotating variety of new strains in the form of vigorous, healthy clones, the company also aims to help with difficulties that impact the health of plants and yields. To that end, one of the newest Dark Heart services is a “clean plant program,” whereby a grower can submit a plant to the lab and technicians eradicate pathogens, then preserve the sample’s genetics in tissue culture.

In a generic office building not far from Dark Heart’s nursery facility is the company’s tissue culture lab, where plant scientists develop cutting-edge genetic preservation techniques designed to give growers a leg up on the competition. Using a scalpel and an electron microscope, technicians mining for stem cells carefully scrape away the outer layers of a shoot’s stem at the growing tip to uncover the stem cell node, which is about the size of a human hair. Here, hundreds of cells that define the genetic makeup of the plant are exposed. If these cells are captured before they are exposed to the plant’s vascular system—where the majority of pathogens float around—any regenerations will be pathogen-free.

“These are advanced techniques that are hard to perform,” said Grace. “We also use pre-treatments to reduce the pathogen load by causing them to retreat. By doing proprietary testing downstream, it tells us what pathogens are getting through, so we get better and better at eliminating them through this process. It’s a unified program to produce the cleanest and best cannabis plants in the industry right now.”

In a nutshell, tissue culture is a process during which stem cells are transferred to an artificial environment—in this case, a mixture of sugar, gelatin, nitrates, and vitamins—that gives the cells all they need to survive and function. The procedure is complicated, involving twenty to thirty variables, Grace said, but it allows the company to maintain a slow-growing genetic archive of hundreds of strains in a relatively small space.

The cultures are started in test tubes and then transferred to small containers stacked on metal shelves with LED lights mounted above them. This is Dark Heart’s memory bank, where strains that are not in mass production can be stored for up to three years. Over the course of a few months, the plants can be brought out of their culture, putintoa grow plug, and ultimately transplanted into a bigger pot that becomes a mother plant.

The “elite mother block” might sound like a gang of cold-blooded matriarchs from a sci-fi novel, but in Dark Heart’s scheme of things it’s a more innocuous bunch. The elite mothers are a collection of virus-free mother plants that were sprung from their tissue culture habitats and then used to provide cuttings for the company’s commercial clone business. But how do they know these elite mothers are indeed virus-free?

“A nursery is only as good as the number of pathogens they test for, and we have a good screen that other nurseries don’t,” said Grace. “Many nurseries talk about clean plants, but very few talk about what they’re testing for. Most of them test for common viruses that impact tomatoes and tobacco.”

Staking a claim on cannabis DNA

Compared to other plants and animals the cannabis genome isn’t particularly large, although ithas about 800 million base pairs, the building blocks of the DNA double helix. By comparison, the sunflower genome contains 3.6 billion base pairs, which is about twice as many as the human genome. However, the size of a genome doesn’t necessarily relate to the complexity of an organism, and cannabis is unique in the degree of variation among its contents, withmore than 400 compounds that belong to the phytocannabinoid and terpene classifications.

In January 2018, a team of scientists at Sunrise Genetics presented the first completed cannabis genome map, which gives researchers access to a comprehensive view ofthe ten pairs of chromosomes in cannabis. In order to determine the functions of specific genes, scientists need to link genotypes with observable traits and find enough correlations to verify the connections. By looking at DNA from cannabis plants with higher yields, for instance, scientists could try to associate those properties with sequenced DNA building blocks called single nucleotide polymorphisms (aka SNPs or “snips”). When snips are identified, breeders may use them to create new strains with specific attributes such as potency, pest resistance, and early flowering.

The more genomic data is analyzed and decoded, the more doctors and patients may be able to accurately match specific strains and/or cannabinoids to specific symptoms and diseases. But with almost 150 cannabinoids and 100-plus terpenes and flavonoids in the mix, the potential combinations will take some time to identify and comprehend.

“The cool thing about cannabis is that it produces all these compounds that are very different and unique, and all of them in multiple ratios,” said Dr. Daniela Vergara, an evolutionary biologist researching cannabis genomics at the University of Colorado Boulder and founder of the Agricultural Genomics Foundation (AGF). “It’s not like aspirin, though, and these different compounds make it hard to bring it into mainstream medicine.”

Of course, this also presents a dilemma of sorts for those who wish to capitalize on a particular strain of cannabis, given that its complex chemical structure is only beginning to be identified and documented.

Open source cannabis?

After decades of ad hoc experimentation during which thousands of strains were crossed with each other, farmers in Northern California have built an unrivaled genetic collection of cannabis. The only problem is, very little documentation exists about how and where strains were created, much less who the descendants may be. Who knows how long it will take to make sense of the twisted genetic puzzle? In the meantime, some companies arehedging their betsby filing patents.

Kenneth Morrow is the founder of Trichome Technologies and author of Marijuana Horticulture Fundamentals. During his thirty-five years in cannabis research, he has become an expert on everything from breeding to hash-making. Morrow argues breeders in Northern California need to be more careful about protecting their most valuable genetics: European seed banks, among others, have utilized Humboldt genetics to create commercial seed lines that are licensed to some of the biggest Canadian companies, which are exporting products internationally.

“The big picture is that Humboldt growers work their asses off to find a good copy of a phenotype and breed it and find their winner and take it to [The Emerald] Cup and sell seeds,” he said. “They take those genetics they worked so hard to isolate and erode their strategic advantage by making them public property. Some say that’s altruistic, which I agree with, but this is what happens when you put these strains up for sale.”

So, the answer is to patent potentially valuable and unique strains, right?

Cannabis patents already have been granted. The most significant—U.S. Patent No. 9,095,554 (“the ’554 patent”), awarded in 2014—belongs to BioTech Institute LLC. The summary abstract states, “The invention provides compositions and methods for the breeding, production, processing, and use of specialty cannabis,” and the patent describes in detail cannabis strains that have both THC and CBD, plus certain terpene profiles. Many cannabis plants fall within the THC, CBD, and terpene ratios outlined in the company’s multiple patents, and should they be enforced, growers would have to pay royalties or stop growing any strains that match the profile in the patent.

The Open Cannabis Project is one of several groups involved in documenting genetic and chemical data for all the cannabis varieties in existence today, and this “prior art” would help prevent the USPTO and other international patenting bodies from granting intellectual property rights that would cover existing varieties. Holmes believes there are better ways to generate revenue from unique cannabis genetics than filing patents, such as bringing new strains to market only as flower—so other companies can’t clone them—or licensing special strains to a discrete set of growers.

“Patenting is expensive and takes a long time,” said Holmes. “With seed-to-sale tracking you can identify cheaters in the supply chain, so while breeders need to monetize their work, patents may not be the best way of doing that. When we eventually have stable seed lines and tools to track who’s growing what, people will license varieties and there will be lawsuits and it will be messy for a while.”

Will the real Jack Herer please stand up?

One of the most compelling aspects of the Phylos Galaxy is that it can help determine relationships between cannabis strains in the same genetic families and help sort out which OGs, for instance, have the strongest correlation to each other. However, identifying the “true” and/or “original” version of any strain is not possible.

“People always ask, ‘How do you know this strain is what it is?’” said Holmes. “But it’s a fool’s errand to answer that, because unless there is a benchmark there’s no way of knowing.”

Looking at the Phylos Galaxy, you can identify where a sample strain lands in the galaxy, and some strains might have a huge cluster where everyone agrees on the original breeder. Sometimes there are multiple clusters of the same names. “It’s not our job to say this is the real Girl Scout Cookies,” Holmes said. “All we can say is that you’re in one of the Cookie clusters and you can see who submitted that and draw your own conclusions. So, for anyone to say ‘this is

Blue Dream,’ I don’t think it will be quite that simple. For legacy varieties it will be very complicated, because there has not been much professional, modern breeding and it’s just a very unusual plant population, so no one knows what’s what. About half the time they do know what’s what, but the rest of the time they are completely wrong.”

“The big picture is that humboldt growers work their asses off to find a good copy of a phenotype and breed it and find their winner and take it to [the emerald] cup and sell seeds.”

—Kenneth Morrow, founder, Trichome Technologies

If companies are allowed to patent strains, they may wellbe able to enforce patent claims against other companies that grow that same strain. At that point, the retail market may start to look more like the craft beer and wine industries, where consumers have allegiances to specific flower varieties and brands.

“You can go to any store in Vegas and buy Blue Dream,” said Morrow. “But if you have something unique and special, it’s different. Cannabis will soon get very proprietary in that way. Everything in the public domain, you can take that body of work and do what you want with it. So, people who create superior products by breeding something unique will be able to patent it.”

As the Phylos Galaxy fills up, growers will be able to verify their “True OG” cut at least falls within a similar group of True OG strains. In this fashion, growers and consumers alike will get a better sense of which traits they should expect from strain to strain. While the craft side of the industry tries to carve out as much of the market as it can with new and exotic cultivars, the strains that become most popular and widespread likely will be strains the commercial industry deems best for their production practices.

“Going forward, the industry will rely more on seeds—once we’ve done the inbreeding work—and people will stop growing [cannabis] in these ridiculous spaceships in Canada,” said Holmes. “They’ll start growing it outdoors and in greenhouses in Kentucky and Colombia. Then it will become a modern crop.”

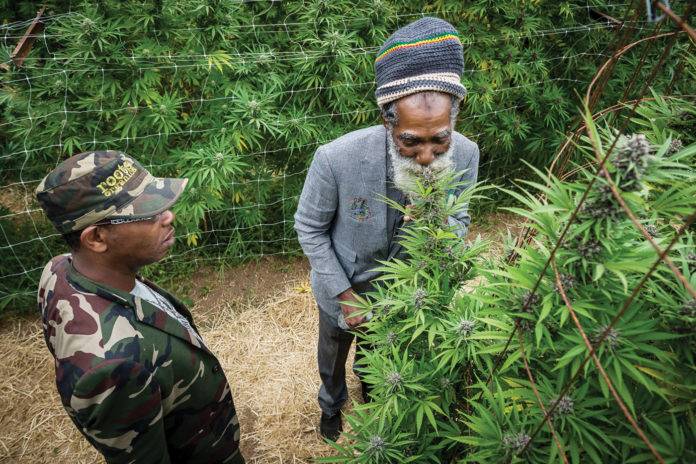

More photos by Mike Rosati: