Just a decade or so into North America’s adult-use cannabis experiment, we have a strong sense of where the biggest companies (multistate operators, or MSOs) plan to assert their dominance. As states make the inevitable shift from illicit to medical or recreational sales, major operators have been gobbling up as many retail and cultivation licenses as possible, hastily assembling vertical infrastructures in a bid to control regional markets and enter the federal legalization era on strong footing.

They have proven adept at raising and deploying capital to accumulate cultivation, manufacturing, and retail operations, but they have been notably less bullish on cannabis product brands.

“So far, MSOs have been acquiring to either go deeper in states they already operate in, enter new states, or expand their capabilities,” said Dai Truong, managing director at Arlington Capital Advisors, an investment firm active in the cannabis space. Truong also is the editor of the newsletter “Highly Objective,” which reports on industry merger and acquisition (M&A) activity.

“As it relates to brands, they have adopted a kind of wait-and-see approach,” he continued. “They haven’t been eager to acquire brands because they believe that, while they will matter in two to three years, today’s consumer demand comes down to pricing, consistency, and product availability. But they are definitely on the path, and they won’t be ignoring them for long.”

While operational M&A activity is taking the lion’s share of MSOs’ capital and attention, the first batch of great cannabis brands is emerging. Cookies is barnstorming across the country, commanding lines around the block for the brand’s high-potency exotic drops. Cann is surfing on a tsunami of hype through major cosmopolitan markets and demonstrating viability for the beverage category. Edibles powerhouse Kiva continues its national expansion beyond its home state of California with a patchwork of regional licensing partners. This is the first wave of truly national brands, and there will be many more coming behind them.

In mature markets, retailers are positioning brands in out-of-home marketing campaigns. Online delivery platforms are touting the brands they carry as consumers seek greater product selection. New direct-to-consumer opportunities are creating the overdue brand loyalty for which cannabis marketers have yearned.

Together, these signs indicate brands are in ascendance, particularly as consumers become savvier and sample their way through dispensary menus. If emerging markets quickly catch up with legacy markets, demand for a wide selection of the hottest products from across the country will follow.

How will MSOs—who are positioning themselves as the retail gatekeepers in many states—compete with one another to create, license, distribute, and/or acquire the first generation of national cannabis brands? Do any of them have a future household name in their current portfolio? And what role will they play in developing the great consumer packaged goods (CPG) cannabis brands of the future?

Incidental acquisition

Every MSO has a portfolio of cannabis product brands, many acquired as part of larger deals for a cultivation facility or dispensary in which the brand was a nice-to-have addition. Licensed assets have been the priority, and until recently, brands have been mostly an afterthought.

Jushi, a Florida-based MSO, has acquired most of its brand portfolio instead of developing the assets. The most successful brand in the bunch is The Bank, which the company acquired from Colorado operator The Clinic for $10 million. In this case, it was the talent, intellectual property, and award-winning genetics that drew in the company’s chief executive officer, Jim Cacioppo. “The brand itself didn’t have a tremendous amount of value,” he said. “It has Colorado lineage, which is great, but that’s unlikely to matter that much over time. We liked the team and the flower.”

Cacioppo isn’t convinced of the power commanded by a brand’s name and presence alone. “I would never pay a lot for a brand company, because in cannabis the most important thing is the machine you have to deliver it,” he said.

Even with Beyond / Hello, the sleek dispensary chain Cacioppo considers Jushi’s best asset, the company initially didn’t place value in the brand itself. “We just realized after we bought it that it was better than what we were doing, so we stuck with it and rolled it out,” he said.

Aside from a trio of house brands, Illinois’s Verano also indirectly acquired much of its portfolio. The company’s MÜV product and retail assets came as part of its acquisition of Florida operator AltMed. “We were interested in the whole operation,” said David Spreckman, vice president of marketing and communications. “They were an incredible business with a great team in Florida, operations in Arizona, and a couple hundred thousand square feet of grow, and they did a nice job developing that market and built a very strong brand with great customer loyalty, retention, and engagement.”

Verano has acquired three other brands so far: Vital (edibles and retail) and Hi-Klas (concentrates) as part of a deal for Arizona operator Territory Dispensary, and Agri-Kind, a Pennsylvania flower brand included in a $115 million deal for a cultivation and manufacturing facility. “We recently reached an inflection point,” said Spreckman. “We’re turning a renewed focus to brands and brand development. We’ll look to level out across our footprint where there’s white space in a given state for the brands in our portfolio.”

Ayr Wellness also accumulated the bulk of its fourteen product lines through acquisition of other assets. The MSO is restructuring its portfolio to lead with three budding national brands, including the seltzer Levia, which it recently bought for $20 million. The low-dose beverage currently is available only in Massachusetts and, according to Ayr CEO Jon Sandelman, the product commands an 80-percent market share in the beverage category (impressive given Cann’s presence in the state). The science supporting Levia enticed Ayr, and Sandelman is staunch in his belief the beverage category stands to gain the most when other CPG industries weigh in on cannabis.

“Levia filled a big gap for us,” said Sandelman, who enjoyed a career on Wall Street before switching to Green Street. “The multibillion-dollar hard seltzer craze shows us there has been a paradigm shift from drinking beer all day long to [buying] a low-calorie alternative. And even though cannabis beverages are a tiny part of the market today, that’s not going to last.”

Sandelman believes the cannabis industry is in an “incubation period,” building the infrastructure, establishing the market, and enduring regulatory uncertainty as it waits for major CPG companies to participate after federal legalization. “We’re building out the store brands, the cultivation, and the distribution for them,” he said. “They are allowing us to develop what will become one of the greatest CPG opportunities of our generation.”

The California factor

There is no disputing brands from California are the most developed. The state’s legacy status as the home of cannabis culture has made California a brand in itself. The problem for MSOs is the state is a humbling, capital-intensive market. Most have at least a toe in the water, while others have credible, competitive brands on the shelves.

“Outside of 2018 and early 2019, MSOs have taken the approach of paying attention to California without necessarily going deep,” said Truong. “You can say that about pretty much all the MSOs that have any exposure in California.”

“The average investor doesn’t want large, profitable MSOs going to California, because it’s a slow-growth market that’s more competitive and more of a chore,” said Jushi’s Cacioppo, whose company has a California-based creative team that scouts for ideas to replicate in other markets. “We spent an enormous amount of time trying to understand that market and then develop our versions of California-style products.” Jushi’s Tasteology edibles brand, in particular, is a not-so-subtle version of Kiva’s popular gummies.

Aside from Curaleaf, which heavily invested in California with its acquisition of Select for a whopping $948 million, Cresco is probably the only MSO prioritizing competition in the world’s biggest single market. Cresco’s eponymous flagship product brand (premium flower and concentrates), High Supply (lower-tier flower and concentrates), Mindy’s (top-shelf edibles), Wonder Wellness Co. (edibles), Good News (lower-tier prerolls, vapes, and edibles), Remedi (tinctures and capsules), and FloraCal (top-shelf flower) all are available in the Golden State.

Each of Cresco’s brands were developed in-house (with the exception of FloraCal, which was acquired as part of a deal with Origin House) by a creative team led by former Nike creative director Scott Wilson. The well-executed portfolio speaks to the company’s philosophy of giving consumers a breadth of high-quality choices for all use cases, regardless of current market maturation.

“While, historically, constrained supply led to consumers being forced to buy whatever you wanted to sell them, we just don’t believe that’s the future,” said Chief Commercial Officer Greg Butler. “Consumers and patients are going to have choices, and brands are how you help them make those choices.”

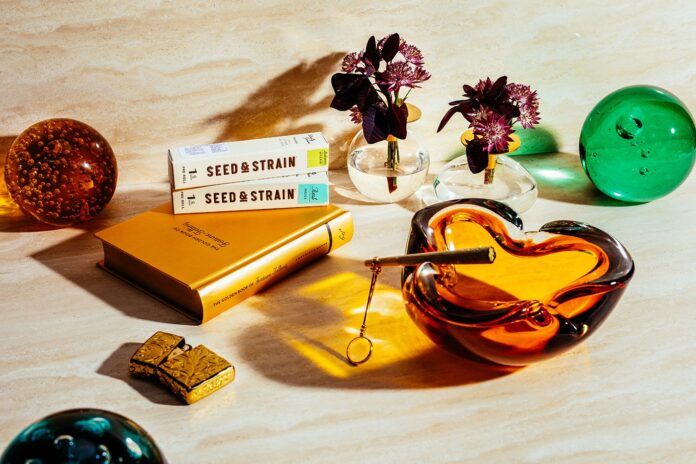

Columbia Care’s flagship California brand is Triple Seven, which came as part of a $69-million deal for Project Cannabis and currently is available in 130 stores in the state. The company is rolling out Triple Seven, Classix—also part of that acquisition—and in-house brand Seed & Strain across its fourteen states as a “good, better, best” vessel.

Columbia Care’s pivot toward building a national brand portfolio has been swift, spearheaded by Chief Growth Officer Jesse Channon. “In fifteen months, we went from being a retail brand with no product brands to having Cannabist (a dispensary chain), which is going to roll out in eighty locations across the country in the next twelve to fifteen months, half a dozen product brands with a growing portfolio, and we’re always looking for more,” he said.

Holistic Industries also has a competitive California brand in Garcia Hand Picked, a collaboration with the estate of Grateful Dead frontman Jerry Garcia. As Holistic tells it, Garcia’s family chose to work with the company because it was the “least douchey” of the MSOs they considered.

“They liked that we really cared about the product and that I was a Deadhead,” said Chief Marketing Officer Kyle Barich, a former pharma ad man. “When the Garcias came to Holistic, we treated it more like an advertising pitch. We had creative ideas fully fleshed out.”

Garcia Hand Picked (flower, prerolls, and gummies) is available in more than 130 stores in California and may have the distinction of being the only “celebrity” brand that transcends its namesake (which is very fortunate for Holistic, as Gen Z consumers—now a bigger market segment than Baby Boomers—weren’t even alive when Garcia died in 1995). “What started out as something for Deadheads is turning into a high-quality flower independent of the Garcia name,” said Barich.

Platinum Vapes is another Cali performer owned by an MSO, acquired outright in 2020 for $60 million by the upstart Red, White & Bloom (RWB). Attracted primarily by the brand’s dominance in Michigan and competitiveness in California, RWB CEO Brad Rogers saw national potential for Platinum. “The brand is larger than life and can easily find a path to a dominant position in any market,” he said. “If you can make it in California and transfer that same brand seamlessly to such a different market like Michigan, you have a winner.”

Rogers believes in powerful brands. He spent the formative years of his career leveraging the brand equity of the Food Network into a themed-CD empire in his native Canada. RWB is the exclusive High Times licensee in Michigan and Florida, scooping up what is perhaps the only true legacy brand in cannabis and reimagining it as a retail store and product line.

Enter Michigan

Michigan, like California, is a tricky state that causes MSOs anxiety. The market’s revenue is expected to double in size, year over year, by the end of 2021, but its unlimited license structure makes the market highly competitive, which some big players don’t like.

That said, fierce competition is precisely what some operators seek. TerrAscend just made a big bet on Michigan’s potential with its recent $545-million acquisition of Gage, the stylish retailer and cultivator led by former Canopy Growth CEO Bruce Linton. In Gage, TerrAscend wasn’t just acquiring a major player with a bundle of retail licenses; the company picked up one of Michigan’s first great homegrown brands and a shrewd licenser of California’s hottest properties, having locked in exclusive deals with Cookies and rising streetwear-adjacent brand Pure Beauty.

“The economics of the deal are strong, but the bigger picture is that we’ll take the Gage brand, the team, and their marketing know-how and apply that to the other states where we operate,” said Jason Wild, TerrAscend’s executive chairman and president of JW Asset Management. “I think there’s going to be a place for the Gage brand in all of our jurisdictions, because these guys have—in my view and in the view of people who really know the Michigan market—one of the best brands and the best operations in the state.”

According to Truong, “Michigan is a key market. I’m surprised more MSOs have not made a strong approach there. We tend to see these companies follow one another, so now that TerrAscend has made their move, I could definitely see another one or two transactions happening in the next six months.”

Truong believes many MSOs cling to the narrative they should enter only limited-license states, steering clear of more competitive markets at this stage of the game. Wild, however, is skeptical of the national potential of brands originating from low-competition states. He sees competition as vital to weeding out products that don’t inspire consumers.

“What I do like about more competitive states is if someone’s doing really well there, it’s because they’ve created a great brand and people like their products, not because it’s just available,” said the pharmacist-turned-investor, who professed liking the entrepreneurial, product-focused nature of states like Michigan.

Most of TerrAscend’s portfolio of vibrant, well-positioned cannabis product brands was developed in-house, with the exception of Valhalla (a legacy California edible), State Flower (premium flower), and Ilera (vapes, tinctures, and topicals), which arrived in a flurry of acquisitions in 2019. Independent of the Gage acquisition, TerrAscend already has inked a deal to license Cookies in New Jersey, keen to capitalize on the unique level of national demand the brand commands at the moment.

Licensing vs. acquisition

Licensing is a less expensive, less risky means of introducing a popular brand to an ecosystem and testing its potential in a new market. Abundant examples exist throughout the industry. In 2019, Florida-based Trulieve agreed to manufacture and distribute Colorado brand portfolio Slang (creator of District Edibles, among others) in Florida, extending the agreement to Massachusetts earlier this year. California concentrate producer Blue River and Colorado-based edible brand binske also were brought into the Trulieve family via licensing deals.

“We have approached licensing by considering both national brand strategy and local market needs,” said Trulieve CEO Kim Rivers. As it relates to binske, Rivers explained an intellectual property model enabled the company to “deliver consistency while allowing for local product modifications, such as the exclusive-to-Florida tinctures we brought to market in 2019.”

The most intriguing of the deals is Green Thumb Industries’ partnership with Cann, which saw the MSO invest in and agree to manufacture and distribute the stylish seltzers across GTI’s Illinois and New Jersey footprint. “We haven’t really seen other MSOs do this kind of deal, so it’s definitely an outlier,” said Truong, who believes the deal could be a sign GTI is becoming too big to innovate, a frequent reality for publicly traded companies. “This begs the question, are these big businesses scrappy enough to build something innovative in-house and take an idea from zero to one? They might be great at one to one hundred, but the bigger you get, the harder that first leap becomes.”

GTI’s compelling brand roster also boasts Beboe (luxury vapes from California; acquired), Dogwalkers (mini-prerolls), Dr. Solomon’s (topicals and tinctures), incredibles (edibles from Colorado; acquired), The Feel Collection (tinctures), and Rythm (flower), which data analysis firm BDSA reported as the second-best-selling brand in the entire country for the first half of 2021 (behind Cresco).

Other MSOs are less interested in licensing, believing either they have the brands they need to compete right now or the brand simply doesn’t add enough value to merit a partnership. “We have chosen not to license brands because we have an extensive portfolio,” said Ayr’s Sandelman. “This will evolve, but today we sell everything we make, so we haven’t had the need to license. But I would never rule anything out.”

Jushi’s Cacioppo is unequivocally against licensing. “You cannot take a brand to a limited state like Pennsylvania or Virginia without going through an MSO,” he said. “It’s just weed. I’m not going to pay you your 20 percent after we’ve put all this money into getting a license.”

Wholesale agreement

Despite strategic differences in other areas, most companies agree about wholesaling, which they rightly consider essential for maintaining growth.

“The only way brands will become regionally and nationally recognized is through wholesale,” said Truong. “Cresco is particularly successful as a wholesaler, and that’s why Wall Street research analysts have applauded them over other MSOs.”

According to Cresco’s second-quarter 2021 financial statements, wholesale sales accounted for 51 percent ($108.7 million) of the company’s total revenue, a 97-percent year-on-year increase. Curaleaf, the biggest MSO by market capitalization, saw 29 percent ($89 million) of total revenue from wholesale, chiefly via Select. Ayr is aggressively pursuing wholesale opportunities and claims the number of stores that carry the company’s products has increased threefold in a year. Roughly 50 percent of Holistic’s revenue comes from wholesale, Barich said. Trulieve recently launched wholesale operations in Massachusetts, Jushi sells to more than 100 stores in Pennsylvania, and RWB recently announced its High Times line (packaged flower and prerolls) is available in twenty-three stores in Michigan.

TerrAscend’s Wild sees wholesaling as essential in markets where retail licenses are limited, such as New Jersey, where the state permits just three per applicant. “If we didn’t sell our products to others, we’d be missing out on a big part of that market,” he said. “But in Michigan, Gage rarely wholesales theirs or Cookies’ flower to anyone, because if you’ve got unlimited license potential and a special product that will draw people, you don’t necessarily have to wholesale.”

Wholesaling is the first step toward national validation for brands, and a litmus test to see whether they could be in high demand in competitors’ stores—not just winners in their own card game.

Columbia Care’s Channon believes having dispensary shelves stocked with in-demand brands, regardless of the parent company behind them, is essential for running a successful store. “We should be carrying many different brands, and the customers should be voting with their wallets as to what it is they want to see in the stores,” he said.

Channon pointed to a Columbia Care store in Colorado that “lost its way” by focusing too heavily on the MSO’s own products. A significant inventory overhaul saw the outlet recalibrate around carrying the largest percentage of top-selling brands and SKUs across the state. “It’s okay to carry other people’s products if you make sure your customers leave happy,” he said. “There’s a timeline on how long you can get away with restricting competition in your store.”

If independent brands have aspirations of scaling beyond their home states, it’s looking increasingly likely they’ll have to do business with MSOs. Kiva’s impressive, if scattered, maneuvering around them (with the exception of a Cresco licensing deal in Illinois) provides a blueprint for an alternative path toward a national footprint for brands, but the strategy is only optimal for those with considerable leverage and revenue. For the rest, forming partnerships with MSOs is the safest path.

That’s good for the MSOs too. Despite what many of them think, the brands in their portfolios probably won’t be the nationally known CPG powerhouses they want them to be. Everyone believes they have a Coca Cola in waiting, and all of them bristle at the suggestion their house of brands may, in fact, be just house brands.

Culture clash

For as long as “cannabis culture” reigns supreme, truly inspiring and groundbreaking cannabis brands are unlikely to come from the top down. As Truong highlighted, innovation happens at the move-fast-break-things end of the market, and none of the massive, cautious companies embody that spirit. They probably shouldn’t; responsibility to their shareholders ought to inhibit willingness to court failure, an important and unavoidable byproduct of innovation.

But that doesn’t mean they can’t play a crucial role in helping the next generation of innovative brands go national. The kingmaker role requires only an honest assessment of where MSOs’ strengths (raising and deploying capital) and weaknesses (creativity and connection to the culture) lie.

“When I was in the investment and M&A team at Anheuser-Busch, we knew we couldn’t build something disruptive in-house because we were a multinational corporation, not a scrappy startup,” Truong explained. “So we would invest and take a minority position in exciting companies, but we would want the right of first refusal so if something was a runaway success, we could at least match any offer that came in.”

Perhaps there’s something in this. GTI’s investment in and licensing deal with Cann is an interesting model other MSOs may benefit from studying: Find cannabis product brands with a lot of potential in an established market that create complementary products to your existing portfolio, and use your capital and operational heft to help them grow nationally.

If you don’t, you might miss out on the next Coke because you were too busy pushing your own branded cola.