Memorial Day 2020 will be remembered as a watershed moment in history. Throughout the holiday weekend, civil unrest exploded in communities across America and around the world to protest the senseless killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and other unarmed Black people whose lives were cut short by law enforcement officers and vigilante racists. A new civil rights movement was born that weekend, but the mood and behaviors unfolded differently from the way they did in the 1950s and ’60s. Hashtags and social media posts were called out for being more platitudes than genuine action, and simply denouncing social injustice no longer was enough. Anyone committed to the cause also needed to back up their words with actions. As people of all backgrounds began to reckon with the reality of systemic racism in the United States, even White allies of the Black Lives Matter movement had to face a difficult truth: They have benefited from a divisive and inequitable system.

The cannabis industry was not spared scrutiny.

Legal cannabis may be a multibillion-dollar industry now, but underlying its prohibitionist history is a well-documented racist agenda that helped fuel the disproportionate targeting, arrest, and incarceration of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). Even today, as the industry grapples with social equity, Black people are nearly four times more likely than White people to be arrested for cannabis possession, according to the report “A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform” (ACLU, 2020). At the same time, White people make up the majority of cannabis business owners in legal markets.

A 2017 study undertaken by an industry publication found only 4.3 percent of owners and stakeholders are Black; 81 percent are White. A City of Denver study in 2020 discovered even though 30 percent of Denver County’s population is Hispanic or Latinx, those groups make up just 12.7 percent of business owners and 12.1 percent of employees in the local cannabis industry. By comparison, White people compose 74.6 percent of the area’s licensed cannabis business owners and 68 percent of employees.

As America embarks upon a long overdue racial reckoning, many within the cannabis community are calling for the industry to turn the mirror inward and face the glaring lack of diversity that helps perpetuate a racist system. To hear their experiences and gain their insights into how the cannabis industry can intentionally address its diversity problem, mg Magazine reached out to Black advocates and business owners. They had a lot to say.

Diversity isn’t a new concept, but not everyone understands the concept or how to achieve it. Simply put, diversity refers to the representation of more than one ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation, or nationality, among other social and cultural groups. Striving for diversity in a workplace or industry requires not only recognizing people’s differences, but also actively embracing them. For the professionals we spoke with, cannabis is similar to other sectors in America where the conversation surrounding diversity tends to center more on ticking boxes than real progress.

“I have found people are very comfortable with folks having a dominant personality when you’re the only [Black person] and you’re getting things done in the name of direction and mission,” said cannabis advocate Dasheeda Dawson, founder and chief executive officer at The WeedHead & Company lifestyle brand. In June 2020, she became Cannabis Program Supervisor for Portland, Oregon’s Office of Community & Civic Life. “But as the mission needs to shift and alter and change—and it certainly does right now in the current movement we are in—those are the times when I start to become the office threat.”

Dawson pursued the cannabis industry after leaving her mark at Target, where she developed the retailer’s plus-size apparel brand Ava & Viv and influenced the adoption of multicultural marketing for the company’s hair and beauty product category. Following her mother’s death nearly five years ago, the New York native relocated to Arizona and found the state’s cannabis program inspiring—but not in a good way.

“Despite having so many patients over 55 and how much [plant medicine] was doing for those patients, it told a really terrible story about cannabis,” Dawson recalled. “I got my medical marijuana card [and] I was like, ‘I can do what I did in corporate America here for brands.’”

Together with her sisters and a team of contractors, Dawson formed a strategy consulting firm to advise government agencies, Indigenous tribes, small brands, and multistate operators in the cannabis industry. But even with her proven track record she continued to face roadblocks, particularly when it came to tapping her own networks.

“I struggle with the hypocrisy in the way White men are able to participate in building [and] extending their networks, and if I’m lucky I get to be a pet and part of a network,” she said. “But the minute I want to extend and build and it’s more BIPOC in its interest because that’s my network, it becomes real problematic on the integration.”

Cannabis activist and Supernova Women co-founder and Executive Director Amber Senter said her experience networking at an industry tradeshow in 2015 was equally revealing. “I’d been invited to this VIP party for the conference and [cannabis activist] Nina Parks was there, and she and I were the only women of color in the place,” Senter said about the event, which took place in a San Francisco hotel. “From there we became friends, and we’d have these discussions around how do we get more people in these rooms? Like, this is totally unacceptable that it’s just she and I; we’re the only brown folks in there.”

A few months later Senter was working as a cannabis application writer, and she invited another new friend, attorney Tsion Sunshine Lencho, to join the consultancy in the same capacity. From there, an even larger discrepancy came into view.

“We’re writing these applications, and all of the groups we’re writing for are White male groups,” Senter said. “We were doing it for Maryland, and Sunshine’s from Maryland. Maryland’s a very Black place, and it just wasn’t reflected in the application process.” The experiences would serve as the catalyst for the three women to join forces and launch Supernova Women, an organization that helps empower women of color to become shareholders in legal cannabis.

For Senter, a veteran of the U.S. Coast Guard who has ownership stakes in multiple California cannabis companies, gaining a foothold in an industry full of people who don’t look like her hasn’t been easy. She cited meeting with dispensary buyers about her brand, The Congo Club. “The Congo Club is the third-best-selling sativa in the state,” she said. “It’s an awesome strain, people love it, it’s got a strong following. And it’s really hard to get on shelves. It’s really hard to get callbacks. You’ve got the buyers that are usually bro-y White dudes that don’t want to talk to somebody like me. You’ve got funders who are looking for someone to invest in that’s like them. They ain’t like me: I’m a queer Black woman!”

Prior to founding the nonprofit organization Minorities for Medical Marijuana (M4MM) in 2016, Roz McCarthy’s twenty-five-year career in healthcare spanned staffing, pharmaceuticals (she spent nine years at Bristol Meyers Squibb) and, ultimately, hospice care. While working with families to secure end-of-life services—much of which is covered by the government if the patient is older than 65—McCarthy learned a great deal about the disparities in her chosen field.

“White families would participate in hospice; they would make decisions together, they were open for the conversation,” she said. “Whereas with Black and Brown families, they were very suspicious. There were already other healthcare issues going on, and you could just see the inequity. It was glaring how there was a big difference in just the concept of healthcare.”

In researching ways to help improve access to physicians and medicine for minority communities, McCarthy became familiar with the medical cannabis program in her home state of Florida. Because the families she worked with generally were leery of traditional medicine, McCarthy believed more education was crucial for cannabis to be considered a resource. But her entry into the cannabis industry was about more than that.

“To be honest, I didn’t necessarily want to be this nonprofit kind of activist,” McCarthy said, “but I was disappointed in the fact I didn’t see some of our traditional civil rights organizations like the NAACP, Urban League, and the National Action Network with Reverend Sharpton. I didn’t see our community-based organizations really stepping in and trying to learn or direct policy to make sure, one, from a healthcare perspective we understood this plant now; two, from a social justice perspective we were looking at how we free people that look like us out of jail since we’re legalizing.”

M4MM offers a variety of resources to underrepresented communities, including veterans outreach program Eagle 22, expungement support through the Project Clean Slate initiative, and high-level application bootcamps for social equity applicants. But for McCarthy, part of upholding M4MM’s mission of “cultivating a culturally inclusive environment” also means holding the cannabis industry accountable. As the rising movement resulted in social media becoming flooded with black boxes and hashtags decrying police brutality and honoring Black lives, McCarthy was disappointed by what she wasn’t hearing from the cannabis industry.

“There were crickets. There was silence,” she said. “We should be the first industry out here saying Black lives matter.” McCarthy drew a line in the sand with a Change.org petition that called on the industry to step up and openly express solidarity with Black lives. By September 2020, the effort had collected more than 10,000 of the requested 15,000 signatures.

“Cannabis has an opportunity—and, I should say, a responsibility—to really figure out how we make this a diverse industry and more inclusive,” McCarthy said.

But if those who work in legal cannabis recognize the disproportionate impact prohibition has had on communities of color, why hasn’t more been done to ensure they have a seat at the table? “It’s like any other industry,” McCarthy said.

In truth, America has yet to make diversity a priority in any of its workplaces. The pandemic has succeeded in exposing the reality that essential workers—who include grocery store employees, warehouse workers and, in multiple legal markets, cannabis retail and delivery staff—are primarily people of color and women.

Meanwhile, in the private sector, fewer than 1 percent of Fortune 500 chief executive officers are Black, and in 2018 the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission found only 3.3 percent of executive or senior leadership roles were held by Black people. According to the study “Being Black in Corporate America: An Intersectional Exploration” (Center for Talent Innovation, 2019), not only have most Black people faced prejudices at work, but they also feel the need to work harder than their White counterparts to get ahead.

Social justice aside, diversity is still in every industry’s best interest. The report “Why Diversity Matters” (McKinsey, 2015) illustrated companies with more diverse workforces perform better financially. McKinsey researchers pointed out in the U.S., “for every 10-percent increase in racial and ethnic diversity on the senior executive team, earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) rise 0.8 percent.” So, in addition to being the right thing to do, diversity makes sense for the bottom line—which should appeal to anyone seeking success in an industry as volatile as cannabis.

“We’re constantly looking for people we can put in the business,” said Jeff Gray, co-founder and chief executive officer at testing laboratory SC Labs. “So we partnered with an organization that supports Chicano and Native American students in STEM [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics] to be able to support their cause, but also be able to bring in the best talent and to have a workforce that’s reflective of the ideals we want to see.”

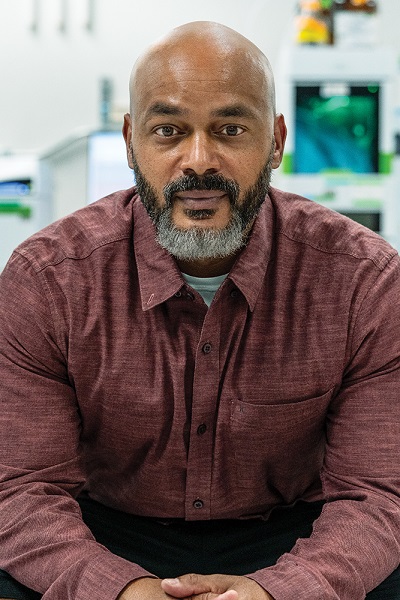

Diversity is a welcome topic for Gray, who spent fifteen years working in various capacities in California’s medical market before launching the lab in 2010. In June, Gray posted an Instagram video calling out the industry’s lack of diversity and equity and reinforcing his company’s ongoing commitment to effect change. For him, the effort includes providing mentorship to social equity applicants through Our Dream Academy and donating 5 percent of his salary to social justice organizations—something he said he has yet to see from other industry CEOs.

“I sit in a room with other CEOs and I’m generally the only Black face,” he said. “I’ve never had an overtly racist interaction with a potential investor; I’ve also never sat in front of an investor who looked like me. In an individual setting, it’s always hard to call it out as racism when you look over the aggregate, but statistics do not lie, right? This isn’t happenstance, and it’s not like we’re just grossly underqualified as a people.”

For Seun Adedeji, Elev8Cannabis co-founder and chief executive officer and the youngest Black man to open a cannabis dispensary in the U.S., the goal is to help his Black employees achieve ownership. “They want to be dispensary owners, cultivators, different things like that, so I use my network and I use my experience and I give them the knowledge they need to really succeed,” he said.

A Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Dreamer who emigrated from Nigeria to Chicago when he was three years old, Adedeji endured three years of traversing the West Coast, educating himself about regulations, researching properties, receiving multiple rejections for everything from licensing to potential partnerships, saving money, and securing funding from friends and family before finally opening his Oregon dispensary at the age of 23. Now that he holds three licenses in Massachusetts, Adedeji aspires to become a multistate operator.

“When I go to dispensaries in Oregon, everyone is really White,” he said. “My store is the most diverse store, period.” In markets that are equally homogeneous, Adedeji hopes more cannabis business owners seek talent beyond their immediate networks. “Having the initiative to hire African-Americans and minorities and making sure minorities get a piece of that pie, I think those are all actionable items.”

What can the industry do right now to improve diversity? According to BIPOC professionals, changing the industry’s relationship with the legacy market is paramount. Senter suggested a way to make that happen. “Lower the taxes [on the industry],” she said. “That will at least give [underrepresented groups] an incentive to participate in the regulated industry. As of right now, there is no incentive. Who wants to come in here and pay tons of taxes and run a business that’s not profitable?”

Even as a new regulator, Dawson believes compliance becoming less of a burden also would go a long way toward increasing diversity. “The cost of doing business or getting licensed feels astronomical and unnecessarily competitive,” she said.

Gray agrees. “We have to raise minority ownership stakes through cannabis licensing,” he said. “We need to create opportunities for minority access and offer economic incentives like tax breaks, access to capital. We need to reduce licensing fees [and increase] support structures that facilitate success.”

For McCarthy, who is looking forward to individual cannabis businesses changing their culture from the inside, the path is clear. She said she would like to see “a commitment to making diversity, equity, and inclusion a priority” starting at the executive level and backed by a written statement that reinforces the commitment and holds the company accountable. To facilitate this, she’d like companies to assign someone to oversee follow-through. “The CEO may not have the bandwidth to drive it, but that person should identify someone within the organization who’s going to drive the conversation, drive the movement, drive the opportunities,” McCarthy said.

Last but not least, she wants organizations to put their money where their mouth is. “Create a budget so individuals who are overseeing this initiative have funds specific to this initiative to be able to participate in and create opportunities for partnership in the community,” she said. Anyone visiting the M4MM website can download “More than a Moment,” a three-page PDF with a list of ways people in the industry can take action to dismantle systemic racism.

Conversations about racism and restorative justice are uncomfortable, but they’re also long overdue. Only through self-reflection can people gain true understanding of how they have benefited from White-majority systems that harm not only BIPOC people but also women, members of the LGBTQ+ community, people with disabilities, veterans, and others.

We’re at a time when everyone, especially those who don’t believe they’ve contributed to systemic racism, must lean into the discomfort and examine their own lives as a crucial first step toward effective allyship. There is no manual for dismantling an oppressive system and there will be missteps along the way, but perfection isn’t the expectation—progress is.

Whether it’s advocating for more equitable regulatory frameworks (even if a company doesn’t stand to benefit directly), looking past the well-worn rich-White-guy network for talent and investment opportunities, directing resources toward mentoring and supporting small operators, or simply showing a minority colleague the respect they deserve at a meeting, even incremental solutions can make a difference.

Cannabis is at a crossroads. If there’s one key takeaway from the racial uprisings of 2020, it’s that there’s no going back. Legal cannabis is unique in that it is an industry rooted in compassionate care and citizen-led activism. We’ve always expected our industry to be better. The difference now is more of us are holding the industry accountable.

But if the goal is to build a truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive industry, the reward will be worth the effort.

[…] diversity intentionally and successfully, mg reached out to Black advocates and business owners. They had a lot to say. Some of their ideas have been adopted, but much work remains to be […]

[…] strong. The industry still has its own internal issues to work out—especially when it comes to diversity and opportunity for all—and the war on drugs, which has devastated many communities, is […]